Maternal guilt and shame in postpartum infant feeding

Overview

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months postpartum and continued breastfeeding up to 2 years postpartum.1 Breastfeeding is associated with positive maternal and infant health outcomes.

But we know that both breastfeeding and formula-feeding mothers experience guilt. The guilts may be concerning family and peers or it may be health care professionals.

The inability to meet breastfeeding intentions is a perceived failure of motherhood, causing shame.6 When a health issue is moralised, those who do not act according to the norm may feel stigmatised.7 Since infant feeding can be moralised, mothers may feel stigmatised based on how they feed their babies. In a study, guilt and shame were associated with self-perception as a bad mother and poorer maternal mental health.8 Many mothers perceived that health professionals ineffectively prepared them for postpartum breastfeeding challenges, leading to self-doubt and anxiety,4 undermining breastfeeding self-efficacy and guilty feelings.9 In another study, breastfeeding mothers felt ineffectively supported by negative comments made by healthcare professionals about their infant and maternal shortcomings associated with feelings of shame.10

Mothers felt breastfeeding guidance and support were inconsistent, causing frustration and confusion,11 and there was an expressed need for better quality infant feeding care. They felt healthcare professionals quickly blamed them for breastfeeding difficulties, leading to guilt for women who were unable to breastfeed and subsequently formula-fed.12 Many felt a lack of respect from healthcare professionals regarding maternal wishes to supplement with formula, which exacerbated feelings of guilt and shame.13 The restriction of formula discussions also led mothers to feel that formula feeding was forbidden and that there was pressure to breastfeed.14

Breastfeeding Grief

Breastfeeding grief often occurs when a mother is unable to breastfeed and has not considered being unable to breastfeed. A sense of loss and anger can occur when expectations are unmet, or one does not get what one wants. When a mother cannot breastfeed, she experiences a loss, consciously or subconsciously. Successful breastfeeding is often linked to success as a mother, which could leave a mother feeling like a failure. A mother may compare herself with other mothers who are successfully breastfeeding and feel something is wrong with her.

Breastfeeding grief may be compounded by a challenging journey to motherhood, including numerous unsuccessful attempts at conception, assisted conception, previous miscarriages (pregnancy losses), and pregnancy and birth complications. Sadly, the medical language used in pregnancy and childbirth could leave a mother feeling like a failure, e.g., an incompetent cervix, a failure to progress in labour, and others. Postpartum difficulties, including parental separation after birth due to admission to Neonatal Intensive Care Unit or Special Care Baby Unit, inadequate breastfeeding support, painful breasts, and breastfeeding difficulties could make it challenging for a mother to initiate or maintain breastfeeding.

Supporting Parents – The Role of Healthcare professionals (HCPs)

When a person experiences loss and grief, undergoing and accepting these feelings is an important part of the healing process. Healthcare professionals should avoid adopting a fix-it or one size fits all approach. Every woman is unique in her breastfeeding grief and how it presents itself. It is essential to employ active listening skills mother's needs, not just to respond but through empathy, imagining their lived experience, and using curiosity to get mothers to express their feelings. The healing process must not be rushed, to avoid invalidating the woman's feelings. It’s important as HCPs that we are choiceful with our language – that we don’t inadvertently add to the burden of shame or grief. They should enquire about the support she has available to her, and the additional help required and refer/signpost her to other support services after obtaining a comprehensive history to prevent the mother from having to tell her story repeatedly, thus re-traumatising her.

A more realistic, non-judgemental, and mother-centred support to minimise guilt and shame experiences for those who breastfeed has been recommended.8 For formula-feeding mothers, providing practical support about how to feed safely and emotional support to those unable to meet their breastfeeding intentions is critical for maternal wellbeing. Also recommended is a shift from a 6 months exclusive breastfeeding to an every feed counts approach to providing breastfeeding support.8

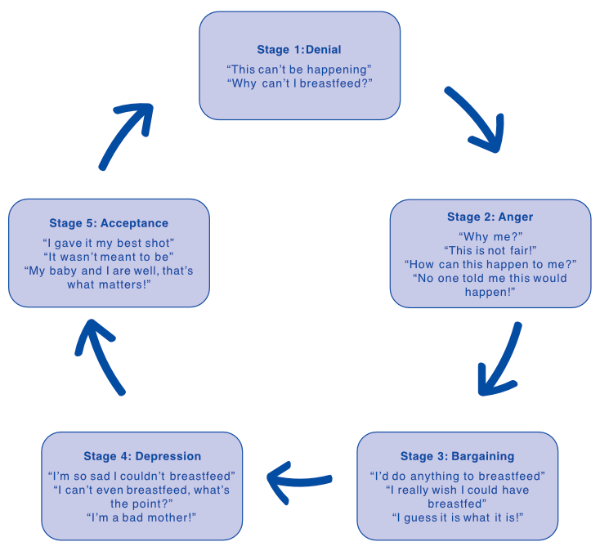

Healthcare professionals must recognise each woman's circumstances and do their utmost to support mothers and their families to have the best experience however they choose to or can feed and raise their babies. They should remind mothers that any amount of breast milk has a positive effect. The longer one breastfeeds, the longer the protection lasts for both mother and baby and the greater the benefits for them. Although mothers are the ones who breastfeed, the effects of being unable to breastfeed impact the whole family – partners and other family members. Consequently, they may require additional support too. When mothers experience breastfeeding grief, sharing and accepting these feelings is an important part of the healing process. Healthcare professionals can use the stages of the grief cycle to support women in healing.

The 5 Stages of Grief (Kubler-Ross, 1997)16

What are the 5 stages of grief:

HCPs can facilitate healing maternal mental health by recognising the significance of guilt, shame, and grief, encouraging communication about their feelings and concerns, and supporting mothers and their families to achieve closure as shown below.

Supporting parents through healing (don’t forget the partner)

-

Allow time to express thoughts and feelings openly.

-

Acknowledge and accept all feelings, both positive and negative.

-

Listen to understand, not just respond

-

Mind your language – avoid blaming/shaming

-

Encourage telling the story of the loss and/or trauma

-

Use the stages of grief to support parents

-

Encourage expression of feelings openly (Crying may offer a release).

-

Seek to identify if there are any related issues, try to address them and encourage coming to a resolution that relieves mothers/parents of any untoward feelings.

-

Enquire about support systems including religious and social groups may provide an opportunity to share experiences with others who have experi¬enced similar losses.

-

Ongoing follow-up and/or referral for further professional help.

Adapted from Labbok (2008)17

Responsive infant feeding

The Baby Friendly Initiative standards recommended responsive infant feeding in recognition of the fact that the terms “demand” or “baby-led” feeding did not adequately describe how successful breastfeeding works.15 In breastfeeding mothers, responsive breastfeeding involves a mother responding to her baby's cues and her desire to feed her baby, recognising that feeds are not just for nutrition but also love, comfort, and reassurance between baby and mother. As such, feeding becomes the first and usually most successful action when responding to a baby's needs (not just hunger). The key message is to feed the baby whenever the mother feels like it, whenever it might help – not just for food but as the first tool to support parenting.

True responsive feeding is not possible in formula-fed babies, as this risks overfeeding. Mothers should be supported to tune in to feeding cues, offering a feed in response to feeding cues, and holding their babies close during feeds. In the early days and weeks of life, parents should be encouraged to give most of the feeds themselves as this will help them to build a close and loving relationship with their baby and help their baby to feel safe and secure.

Healthcare professionals play a crucial role in supporting mothers with infant feeding. Recognising parents have the ultimate responsibility to choose how to feed their babies; they should support their choices endeavouring not to make them feel guilty or ashamed. They would do well to inform themselves about infant feeding guilt, shame, and grief and offer support early to enable women to grieve and heal.

Further reading

-

Robinson, C (2018) Misshapen motherhood: Placing breastfeeding distress. Emotion, Space and Society. 26:41-48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2016.09.008

-

Global strategy for infant and young child feeding. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003 (http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42590/1/9241562218.pdf).

-

UNICEF. (2017). Guide to the UNICEF UK baby friendly initiative standards, UNICEF United Kingdom: The Baby Friendly Initiative. https://www.unicef.org.uk/babyfriendly/

-

NHS UK: Benefits of breastfeeding. Accessed online: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/baby/breastfeeding-and-bottle-feeding/breastfeeding/benefits/

-

Johnson, K. (2013) Maternal-Infant Bonding: A Review of Literature. International Journal of Childbirth Education. 28(3): 17-22

-

Thomson, G., Ebisch-Burton, K., & Flacking, R. (2015). Shame if you do– shame if you don’t: Women’s experiences of infant feeding. Maternal & Child Nutrition. 11(1): 33–46. https://doi/epdf/10.1111/mcn.12148

-

Russell, P. S; Birtel, M. D; Sm.th, D. M; Hart, K; Newman, R. Infant feeding and internalized stigma: The role of guilt and shame. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 51 (9): 906-919. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12810

-

Harrison, M; Hepworth, J; Brodribb, W. (2018) Navigating motherhood and maternal transitional infant feeding: Learnings for health professionals. Appetite, 121: 228-236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2017.11.095

-

Täuber, S. (2018). Moralized health-related persuasion undermines social cohesion. Frontiers in Psychology, 9(909): 1-14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00909

-

Jackson, L; De Pascalis, L; Harrold, J; Fallon, V (2021) Guilt, shame, and postpartum infant feeding outcomes: A systematic review. Maternal and Child Nutrition. 17(3):e13141. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.13141

-

Asiodu, I. V., Waters, C. M., Dailey, D. E., Lyndon, A. (2017) Infant feeding decision-making and the influences of social support persons among first-time African American mothers. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 21(4): 863–872 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-016-2167-x

-

Fox, R; McMullen, S; Newburn, M. (2015) UK women’s experiences of breastfeeding and additional breastfeeding support: a qualitative study of baby café services. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 15:147-158. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-015-0581-5

-

Lagan, B. M; Symon, A; Dalzell, J; Whitford, H. (2014) “The midwives aren’t allowed to tell you”: perceived infant feeding policy restrictions in a formula feeding culture – the feeding your baby study. Midwifery. 30(3): e49-e55 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2013.10.017

-

Fahlquist, J. N. (2016) Experience of non-breastfeeding mothers: norms and ethically responsible risk communication. Nursing Ethics. 23(2):231-241 https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733014561913

-

Hvatum, I; Glavin, K. (2017) Mothers’ experience of not breastfeeding in a breastfeeding culture. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 26(19/20): 3144-3155. http://dx.doi.org.liverpool.idm.oclc.org/10.1111/jocn.13663

-

Crossley, M. L. (2009) Breastfeeding as a moral imperative: an autho-ethnographic study. Feminism & Psychology. 19(1): 19(1), 71–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353508098620

-

Kübler-Ross E (1997) On Death and Dying. Scribner Classics, New York, NY, USA

-

Labbok (2008) Exploration of Guilt Among Mothers Who Do Not Breastfeed: The Physician's Role. Journal of Human Lactation. 24 (1): 80-84. doi:10.1177/0890334407312002

IMPORTANT NOTICE:

We believe that breastfeeding is the ideal nutritional start for babies, and we fully support the World Health Organization’s recommendation of exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life followed by the introduction of adequate nutritious complementary foods along with continued breastfeeding up to two years of age. We also recognise that breastfeeding is not always an option for parents. We recommend that healthcare professionals inform parents about the advantages of breastfeeding. If parents choose not to breastfeed, healthcare professionals should inform parents that such a decision can be difficult to reverse and that the introduction of partial bottle-feeding will reduce the supply of breast milk. Parents should consider the social and financial implications of the use of infant formula. As babies grow at different rates, healthcare professionals should advise on the appropriate time for a baby to begin eating complementary foods. Infant formula and complementary foods should always be prepared, used and stored as instructed on the label in order to avoid risks to a baby’s health.